Toby Keith’s songs accomplished, for some, what great art is intended to: They sustained people in challenging times, particularly U.S. service members and their families during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq after 9/11.

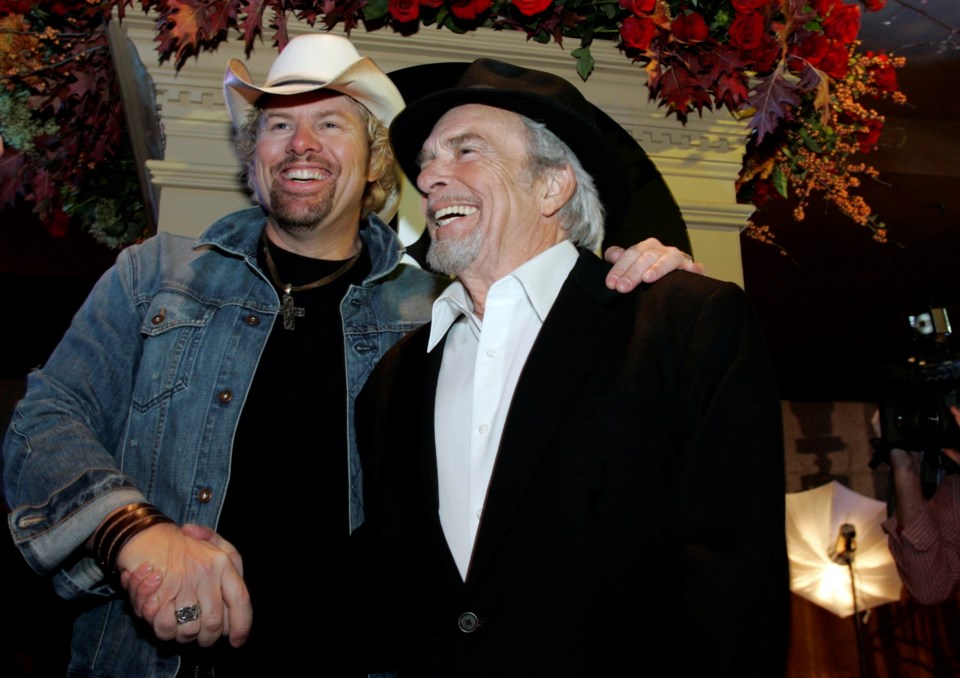

FILE – Toby Keith, left, shakes hands with Merle Haggard at the 54th Annual Broadcast Music Inc. Country Awards, Saturday, Nov. 4, 2006, in Nashville, Tenn. Keith’s hit ”As Good As I Once Was” won country song of the year, and Country Music Hall of Famer Haggard was honored as an icon during the BMI Music Awards. Like Toby Keith, Haggard was politically enigmatic. And while Haggard became a hero among conservatives, he later backed prominent Democrats. (Michael Clancy/The Tennessean via AP, File)

FILE – Toby Keith, left, shakes hands with Merle Haggard at the 54th Annual Broadcast Music Inc. Country Awards, Saturday, Nov. 4, 2006, in Nashville, Tenn. Keith’s hit ”As Good As I Once Was” won country song of the year, and Country Music Hall of Famer Haggard was honored as an icon during the BMI Music Awards. Like Toby Keith, Haggard was politically enigmatic. And while Haggard became a hero among conservatives, he later backed prominent Democrats. (Michael Clancy/The Tennessean via AP, File)

NORFOLK, Va. (AP) — Toby Keith’s songs accomplished, for some, what great art is intended to: They sustained people in challenging times, particularly U.S. service members and their families during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq after 9/11. For others, Keith’s work sowed division and was blindly patriotic — a wedge that deepened America’s cultural fault lines.

Keith, who died Monday of stomach cancer at age 62, is being celebrated for his immense catalog across a diversity of subjects, from small-town heartache to his preference for red Solo cups. But in the fractured political landscape of 2024 America, it’s the long-tail legacy of “Courtesy Of The Red, White And Blue (The Angry American)” that may be remembered most.

For many in post-9/11 America, the 2002 song caught the mood. It featured the lyric: “We’ll put a boot in your ass. It’s the American way.”

Keith’s steering of his music into overt nationalism defined his career and helped set country music — one strain of it, at least — on a more political path that continues to this day in the music of folks like Jason Aldean on the right and Jason Isbell on the left. And yet many observers say it would be unfair to dwell only on those pages from Keith’s songbook.

“You have to recognize that (Keith) was a good songwriter, and that there are songs there to love no matter what political stripe you are,” says Chris Willman, who wrote the 2005 book, “Rednecks and Bluenecks: The Politics of Country Music.”

Willman says some people are struggling with Keith’s legacy because of his overtly political songs. But the man also wrote funny tunes about male virility and smoking marijuana with Willie Nelson.

“You almost want to get defensive of him when people are making it all about a handful of songs,” says Willman, chief music critic for Variety. “And yet at the same time, I totally get where people are coming from. And I’m not sure I disagree with them when they say that he had some negative effect in terms of making country music more about angry Americans.”

COUNTRY MUSIC HAS ALWAYS HAD A POLITICAL THREAD

Country music has never been immune to the nation’s social and political forces, says Amanda Marie Martinez, author of the upcoming “Gone Country: How Nashville Transformed a Music Genre into a Lifestyle Brand.”

The genre emerged during 1920s Jim Crow America, when music executives traveled to the South and recorded along racial lines, establishing the myth of country music as “exclusively white culture,” Martinez says. Conservatives have looked to country music over the decades to voice political beliefs and react to social change.

In the Vietnam War era, Merle Haggard sang “Okie from Muskogee” — an anti-progressive number in which he sings, “We don’t burn our draft cards down on Main Street.” And while Haggard became a hero among conservatives, he later backed prominent Democrats. The man who supported Ronald Reagan and performed for Richard Nixon would pen songs to promote Hillary Clinton and commemorate Barack Obama’s inauguration. He also sang, “Let’s get out of Iraq.”

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/7ERAF6QZFBDQ5EIWFDKYNB25HE.jpg)

Like Haggard, Keith was politically enigmatic. He was a registered Democrat until 2008. He played at events for Presidents George W. Bush, Obama and Donald Trump.

“If we look for a kind of consistency throughout his career, it’s his class politics,” says Joseph M. Thompson, author of “Cold War Country: How Nashville’s Music Row and the Pentagon Created the Sound of American Patriotism.”

“He’s aware of his humble roots,” Thompson says, “and it is who he sings for.”

‘COURTESY OF THE RED, WHITE AND BLUE’ WAS A POST-9/11 ANTHEM

In the weeks after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, the nation felt somewhat unified. In that environment, “Courtesy” worked like traditional folk music in the way it reflected how many people felt at the time. And more musicians started writing songs that actually addressed wartime in near real time.

For instance, Alan Jackson penned his introspective “Where Were You (When the World Stopped Turning)” about 9/11. It lacked the incendiary revenge in Keith’s anthem, although Jackson sang that he couldn’t tell you the difference between Iraq and Iran. There also were Darryl Worley’s “Have You Forgotten?” and Clint Black’s “Iraq and I Roll,” among others.

Keith’s song was by far the most popular. And it was at least partially bolstered by a public feud with The Chicks, then known as the Dixie Chicks, over Natalie Maines’ opposition to the U.S. invasion of Iraq. Maines called Keith’s song “ignorant,” while Keith began performing in front of a doctored photo of Maines with Saddam Hussein.

KEITH WAS A FAN OF THE MILITARY, AND VICE VERSA

In the years following “Courtesy,” Keith participated in 18 USO tours, performing for more than 250,000 service members in his lifetime. John A. Lucas, a U.S. Army veteran who served in Vietnam, says Keith’s songs celebrated military personnel and their families in a fresh way.

“His songs speak to the men and women who win our wars,” says Lucas, 80, who lives outside Richmond, Virginia, and now writes a personal blog on Substack, “Bravo Blue.”

Lucas says Keith’s songs resonated when his son deployed to the Middle East, including Iraq, several times in the 2000s as a member of the U.S. Army’s special forces. Lucas says he and others sent CDs with Keith’s song, “American Soldier,” to the wives of the men serving with his son. Lucas wrote Keith for permission; Keith approved.

Lucas says “Courtesy” also spoke to people in uniform not unlike the way The Animals’ more oblique “We Gotta Get Out of this Place” did during the Vietnam War. “Courtesy,” says Lucas, packed a powerful punch.

“I think some people use it as a reason to say, ‘Well, this is not a very nice song,’” Lucas said, referring to the “boot in your ass” line. “But I’m going to tell you that that resonates with an Army infantryman. He’s talking to the Taliban.”

KEITH’S MUSIC CONNECTS TO TODAY

Last summer, Aldean released the biggest hit of his career, the controversial “Try That In a Small Town.” The music video shows Aldean performing in front of a Tennessee courthouse, the site of a 1946 race riot and a 1927 mob lynching of an 18-year-old Black teenager.

People called the video a “dog whistle”; others labeled it “pro-lynching.” The outcry mobilized conservatives, whose support brought the song to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100.

Willman, the Variety critic, sees a through-line from Keith’s “Courtesy” to Aldean’s “Try that in a Small Town” or Oliver Anthony’s “Rich Men North of Richmond.” Keith “emboldened others in country music to think viewpoints that might be perceived as angry and conservative were okay to express,” Willman says.

That anger, he says, is part of Keith’s legacy because it led some musicians to think, “Yeah, there’s a market for this kind of righteous rage.”

Pat Finnerty, who makes a YouTube show called “What Makes This Song Stink,” also sees similarities between “Courtesy” and “Small Town.”

“If we’re using wrestling analogies — and why shouldn’t we — Toby Keith is the Hulk Hogan,” Finnerty says. “If Hogan’s move was the leg drop, Keith’s would be the flag. He is the Hulk Hogan of this brand of, ‘We’re Americans. We’re the best country in the world. And we can never do any wrong.’”

Finnerty, 43, of Philadelphia, produced an hourlong video on why he thinks “Small Town” is a terrible track. The thing about “Small Town” and “Courtesy,” Finnerty asserts, is that each feels calculated, as if it were written only to make money. Keith capitalized on 9/11, while Aldean exploited the nation’s cultural divide.

“If you took ‘Hey Jude’ and made it about mufflers, it’d still be a great song,” Finnerty says. “But if you took ‘Small Town’ and did that, it wouldn’t work. It’s only about the lyrics in these songs that is grabbing attention.”