Alpine’s drop to the bottom of the Formula 1 field at the start of this year was one of the biggest surprises we have had so far in 2024.

While the Enstone-based team is chipping away in taking off weight and adding aero performance to its A524 to get itself further up the grid, it is still far away from the lofty heights that parent company Renault wants to see it reach.

Indeed, when the decision was made last summer to axe team principal Otmar Szafnauer and replace him with Bruno Famin, it was triggered because of an impatience to get back to the front by senior management that did not believe it would take as long as they were being told.

But rather than the change bringing about a fast-tracked surge forwards, things instead have gone in the other direction. And the reasons for that have prompted much debate, with clear differences of opinion depending on who you speak to.

But beyond the specifics of why things went wrong last winter, Szafnauer himself says that what is playing out with Alpine is symptomatic of one of the common mistakes that car manufacturer teams made: too much meddling from above!

Szafnauer, who during a year out of team involvement has helped create new itinerary management app EventR, thinks that a common theme of successful works efforts is that the road car element stays well away from day-to-day F1 involvement.

So, with Renault CEO Luca de Meo playing an active part in pushing on with the car company’s F1 ambitions, Szafnauer suggests that failure starts at the very top.

Asked if Renault understood what it took to be successful in F1, Szafnauer said: “Not from what I saw.

“I think the best thing, and not just Renault but for big car companies to do – and I’ve seen it a lot, even with car companies that have racing as part of their DNA: they shouldn’t meddle. Leave it! It’s so much different from a car company, you should just leave it to the experts.”

Luca de Meo, CEO, Renault Group

Photo by: Michael Potts / Motorsport Images

Szafnauer said that while there appear to be many common themes between racing ambitions and selling road cars, he thinks that teams and auto makers operate in completely different ways.

“I mean, the only similarities are you have five wheels on a car and five on a racing car – you have four wheels and the steering wheel. And that’s it. The rest is so different.

“You call them a car, but the technology development is different, the top technology you use is different. The level of the engineering that goes into it is different. The level of the education of the engineers is different.

“When I was at Ford Motor Company, for example, they had two management paths when I was there. One, you could take a technical management path. So, if you’re a PhD in mechanical engineering or aerodynamics, you were in stock.

“You could take a technical management path as opposed to a managerial path. And there weren’t that many PhDs in a huge company in engineering.

“I remember when I was at British American Racing, I think it was Gary Savage [who] once said: ‘We’ve got more doctors here than a local hospital’. Which is true, and they don’t come from mediocre universities. They’re all from Oxford, Cambridge, or Imperial [College London].

“So, A, they’re super bright. B, they’re educated to the highest level, in Formula 1. And most importantly, they love the sport, which is why they’re there. So, they’re motivated like hell to win.

Jacques Villeneuve, BAR Honda 003 talks with Olivier Panis, BAR Honda 004 and his engineers

Photo by: Sutton Images

“You don’t get that in car companies. I’m not saying this just about Renault, but I will say it about Ford where I was. And we used to have a saying: Ford Motor Company didn’t make cars, it made careers!

“When you were there, you cared about the car programme you’re on, but you cared more of your career. Whereas in Formula 1, you just care about on-track performance. And that’s a significant difference.”

Attracting new talent

Szafnauer thinks the interference and meddling has not only short-term consequences in not allowing teams to get on with the job of creating better racing cars, but also longer-term implications due to more instability and uncertainty, because it becomes harder to attract the quality staff needed to move forward.

“Forget Alpine, right, because this can be for any team,” he said. “But you go to a guy who is valued, is doing a good job, is performing and say he’s at Red Bull, a senior aerodynamicist, and you want him. He’s winning, he’s got Max [Verstappen] and Checo [Perez]. He’s going to get a nice big bonus. You know, everything.

“So how do you get him to move? One of the things that I used to always do is offer him a promotion that he otherwise might not get at Red Bull for a few years, because the guys above him are also doing a good job and you don’t want to disrupt the structure.

“I used to always say: ‘You know, come with us and go on the journey – and you’ll have a bigger role to play on the journey of where we are to where we’re going than you do there. And the bigger role is because you got a bigger job.’ So that’s how I used to try to attract them.

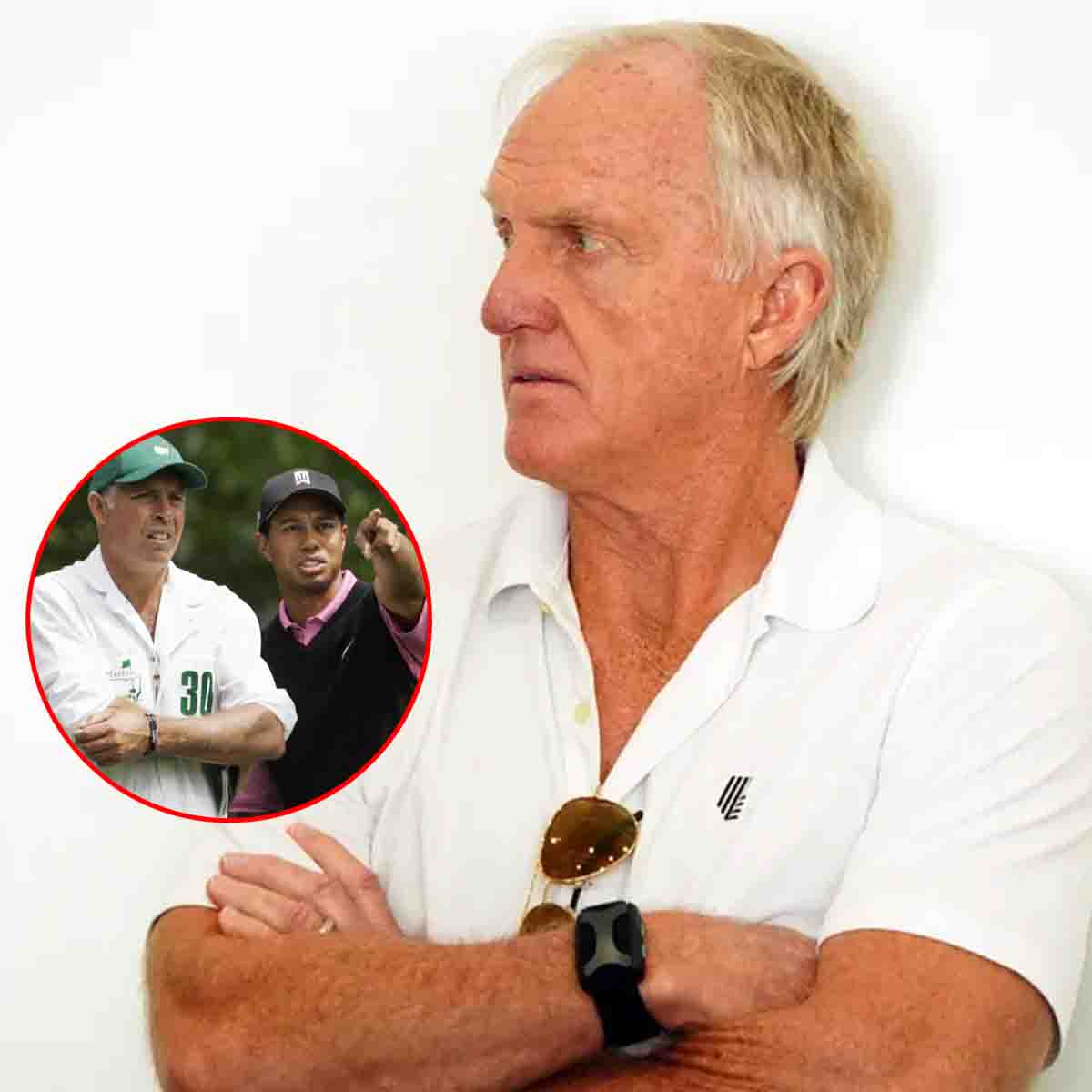

Otmar Szafnauer

Photo by: Alister Thorpe / GP Racing

“Then you also need to make sure that it’s a good place to work. And what does that mean? It means different things for different people.

“For some people, a good place to work means ‘I get paid more’, thank you very much – rest of it is bullshit. For others, that means ‘you recognise my efforts more’. You know, you’re the boss, talk to me, and you know, some people like that.

“You’ve got to understand the individual, what they really want, and then make sure you deliver it in an honest way. And then they come.”

The fault for current failings

Alpine team principal Bruno Famin was drafted in as Szafnauer’s replacement and made some quite pointed remarks recently about where the blame lay for the squad’s current difficulties.

In an interview with the official F1 website, Famin said: “The car we have now is the result of previous management.”

That statement did not go down well with Szafnauer, who says that the timing of his departure before the summer break last year meant that there was no crossover between his running of the outfit and the squad’s 2024 challenger.

“We have limited CFD and wind-on time and geometries,” said Szafnauer. “So, you can’t have three wind tunnels, you can’t even use one wind tunnel to its full capacity, probably just half. As well as CFD. So, because of it and the way the reporting structure goes, I think we report every eight weeks.

“So almost everybody works on the current car up until the [summer] break. And then depending how quickly you can produce the findings by then, some of those upgrades come as late as Singapore if you can produce them quicker.

“Generally, Singapore is your last big upgrade and that last big upgrade that you bring was conceived in June, July.

“After the break, everyone switches to next year’s car. And when it’s next year’s car, you know, you learn stuff about this year’s car, you might change a tub, you might change geometry, you might go from pull-rod to push-rod [suspensions], you know, you change stuff. And when you change it, you mainly change it for aerodynamic benefit.

“So now you start your model changes and you’re starting to do different experiments that don’t necessarily apply to this year’s car. It’s what happened at Renault.

“Alan [Permane] and I left in July, and after we left is when they started on next year’s car. And Pat too, Pat Fry had resigned by then as well.

“So, to the uninformed [audience], you can say: ‘Hey, all these problems were caused by those guys’. But I don’t think so…”

Read Also: