Although this is not the current Comet Lemmon, a previous comet observed in 2013 and found by the same telescope bears a similar appearance: a green glow with a long, thin tail. Credit: Ben (Flickr)

Friday, November 10Comet C/2023 H2 (Lemmon) passes closest to Earth late today, coming within 0.19 astronomical unit, or AU, of our planet. (One AU is the average Earth-Sun distance of 93 million miles [150 million kilometers].)

That means the comet will be at its brightest for the next few days; it’s recently been reported at 6th magnitude but may brighten even more — up to 5th magnitude or so, by some estimates. This puts it squarely in easy binocular range, and it’s up most of the evening in a moonless sky — excellent conditions for nabbing it.

Tonight, Comet Lemmon is in Hercules, which sits just below the bright star Vega (currently the lowest of the three points in the Summer Triangle asterism) in the west after sunset. The region is slowly setting but, thanks to the early sunsets at this time of year, remains visible until around 10:30 P.M. local time.

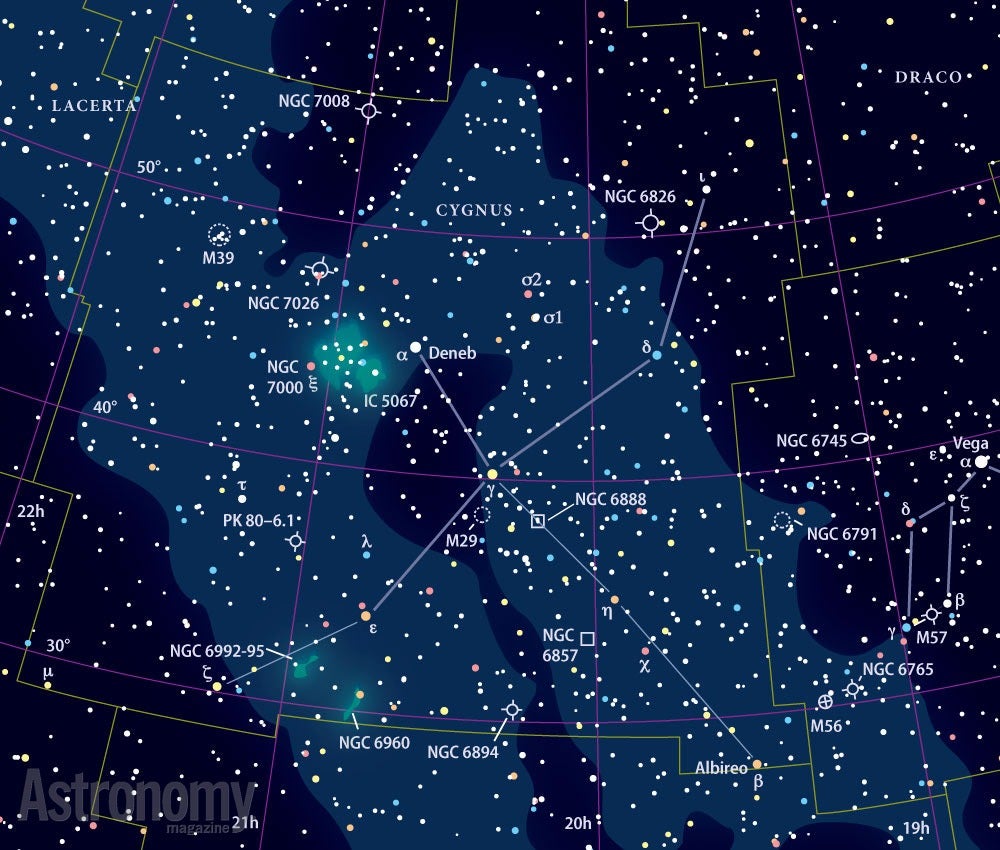

This close to Earth, Lemmon appears to rapidly move through the sky, covering roughly a quarter of a degree each hour. It’s moving southeast through Hercules toward Aquila (to Hercules’ upper left in the sky), which houses Altair, the second-highest star in the Summer Triangle as it sets each night. Check out the chart below for the position of the stars tonight at 6 P.M. local time, and the specific position of the comet relative to those stars at 7 P.M. EST. At that time, Lemmon will lie just below the rough midpoint of a line drawn between Vega and Aquila, in northeastern Hercules and about 7.4° northwest of 3rd-magnitude Zeta (ζ) Aquilae. Note that while the stars will appear in roughly the same place at 6 P.M. from any location, the comet may have moved, depending on your time zone and whether you look before or after 7 P.M. EST specifically. Lemmon is moving from northwest (earlier times) to southeast (later times).

This chart shows the position of the stars and Comet Lemmon in the west on November 10, 2023, at 6 P.M. local time. Note the comet may be in a slightly different position, depending on your time zone, as it is moving quickly across the sky. Credit: Alison Klesman (via TheSkyX)

Most binoculars — though the bigger the better, for easier viewing — or any small (or larger) scope will bring the comet’s fuzzy coma into view. Astrophotographers have been catching its bright green glow and thin tail as well.

Lemmon should be bright and easy to find for at least the next several days. You can check out this article for more details and a chart of its position through November 13.

Sunrise: 6:39 A.M.Sunset: 4:48 P.M.Moonrise: 3:47 A.M.Moonset: 3:28 P.M.Moon Phase: Waning crescent (7%)*Times for sunrise, sunset, moonrise, and moonset are given in local time from 40° N 90° W. The Moon’s illumination is given at 12 P.M. local time from the same location.

The famous Blinking Planetary (NGC 6826) in Cygnus the Swan lies 2.6° southeast of the magnitude 3.8 star Iota (ι) Cygni. Credit: Astronomy: Roen Kelly

Saturday, November 11With no Moon to interfere, let’s track down a stunning deep-sky object with a surprise in store. After dark, look to Cygnus the Swan, still high in the west early in the evening. This constellation houses our target: the Blinking Planetary Nebula, also cataloged as NGC 6826.

The easiest way to find this object is to first note the bright star Deneb, which marks the Swan’s tail and the highest star in the Summer Triangle as the asterism sets. From there, drop down toward the horizon a bit to find 4th-magnitude Iota (ι) Cygni. The Blinking Planetary lies 2.6° southeast of Iota, or just under 5.5° due north of 3rd-magnitude Delta (δ) Cyg. Check out the chart above for help locating it.

The nebula itself is a good 25″ across and glows softly around 9th magnitude. A small to medium telescope will show it best, with larger apertures pulling out slightly more light. But the clue to its surprising nature is in its name — this nebula appears to “blink” on and off, depending on how you look at it!

What does that mean? First, look directly at the nebula. It will appear bright and compact, perhaps almost starlike. You’re mostly picking up light from the nebula’s central star, which has thrown off the shells of gas now glowing as the nebula itself. Then, look slightly away from it, toward the edge of your eyepiece’s field of view. Don’t move the telescope, just your eye, so you’re looking at the nebula not directly, but out of the corner of your eye, in the periphery. The central star should disappear, and instead you’ll see the larger, fuzzier nebula much more clearly! Switching between direct and averted vision makes the star and nebula swap center stage in your visual field, so the effect is that the nebula itself appears to blink brighter and fainter, and smaller and larger. Give it a try!

Sunrise: 6:40 A.M.Sunset: 4:47 P.M.Moonrise: 4:50 A.M.Moonset: 3:50 P.M.Moon Phase: Waning crescent (3%)

Sunday, November 12Jupiter’s small, volcanic moon Io will disappear behind the gas giant’s disk tonight in an occultation that begins shortly before 10 P.M. EST.

You’ll find Jupiter in the southeast this evening well after dark, sitting in southern Aries some 11.5° below that constellation’s brightest star, magnitude 2 Hamal. Jupiter outshines this star by far, as the planet is magnitude –2.9. You should spot it easily. Any small scope will show you the gas giant’s striped face, along with its four Galilean moons.

About an hour before the event starts, around 9 P.M. EST, Jupiter is flanked by Europa nearby and Callisto farther out to the east. To the west, Io is closing in, while Ganymede sits a good distance away. In fact, around this time, the scene appears nearly perfectly symmetric, something that doesn’t happen often!

But keep watching over the next hour and you’ll see Europa pulling away while Io continues to near the limb. The latter disappears around 9:58 P.M. EST, taking just over two hours to cross behind the planet.

But there’s a catch — even once Io reappears, it doesn’t really reappear. That’s because it pops out from behind Jupiter within the planet’s shadow, which stretches to the northeast. You should finally see Io blink back into view around 12:23 A.M. EST on the 13th, late on the 12th in all other U.S. time zones. It will appear not directly off the limb, but a little east of it, showing just how far the planet’s shadow extends. The shadow is actually pretty short right now, given the geometry as the planet recently reached opposition. At other times, it can stretch quite far to one side or the other and moons take a long time to traverse it.

While you wait for Io to return to view, take some time to look at the detailed face of Jupiter. The Great Red Spot is visible around this time, making its way across the planet’s 49″-wide disk. Also visible should be several cloud bands of alternating colors. Take your time to really enjoy all this stunning planet has to offer.

Sunrise: 6:41 A.M.Sunset: 4:46 P.M.Moonrise: 5:55 A.M.Moonset: 4:15 P.M.Moon Phase: New

Monday, November 13New Moon officially occurs at 4:27 A.M. EST, ensuring dark skies to find our target for tonight: the distant ice giant Uranus, which reaches opposition today at noon EST.

At opposition, planets are visible roughly all night long, rising around sunset and setting around sunrise. Uranus currently shares Aries the Ram with Jupiter, which offers a great bright signpost if you’re looking to find the fainter of the two in the sky. Uranus is the farthest planet you can see with the naked eye, as Neptune never gets bright enough to see without optical aid.

Currently magnitude 5.7, Uranus is just at the edge of naked-eye visibility from a dark location. And in fact, trying to spot the planet without any aid is a great way to test the quality of your vision and your observing site! Wait for the sky to grow fully dark, an hour or two after sunset. By then, you should easily spot bright Jupiter, shining at magnitude –2.9, to the upper right of a small, bright cluster of stars: the Pleiades (M45) in Taurus. Uranus lies roughly halfway between these two, just over 2° south-southeast of 4th-magnitude Botein (Delta Arietis). Take your time and look for a faint point of light just to the lower right of this star — that’s Uranus.

Even if you can’t find it with the unaided eye, Uranus is easy to pick up with a pair of binoculars or any telescope. It will look like a small, “flat” star or disk with a slight grayish hue. The planet’s disk spans just 4″ — a testament to its distance of 18.6 AU, or 1.7 billion miles (2.7 billion km) from Earth. In reality, the planet stretches some 31,000 miles (50,000 km) across, or four times as wide as Earth!

Sunrise: 6:43 A.M.Sunset: 4:45 P.M.Moonrise: 7:04 A.M.Moonset: 4:47 P.M.Moon Phase: New

Tuesday, November 14The one-and-a-half-day-old Moon passes 0.9° north of Antares, the bright red giant that marks the heart of Scorpius the Scorpion, at 3 P.M. EST. Unfortunately, the close pass occurs in daylight and the constellation is very low by sunset, meaning Antares may not quite stand out from the twilight before it sets about half an hour after the Sun.

However, you can still try catching the delicate young crescent Moon around sunset, which sits alongside Mercury in the southwest. By 20 minutes after sunset, the pair is just 2° high, so you’ll need a very clear horizon and ideally an elevated viewing site to see them. Mercury will be easier to spot at magnitude –0.5; the small, bright planet sits a tad less than 5° to the right of the Moon, which is just barely 3 percent lit. Binoculars or a small telescope should pick up the thin crescent, which appears lit from the lower right — that’s the direction of the Sun, which lies farther west along the ecliptic. Seeing such a young Moon can be a real challenge with the unaided eye, but like finding Uranus, a fun one to test your eyesight!

Sunrise: 6:44 A.M.Sunset: 4:44 P.M.Moonrise: 8:15 A.M.Moonset: 5:26 P.M.Moon Phase: Waxing crescent (2%)

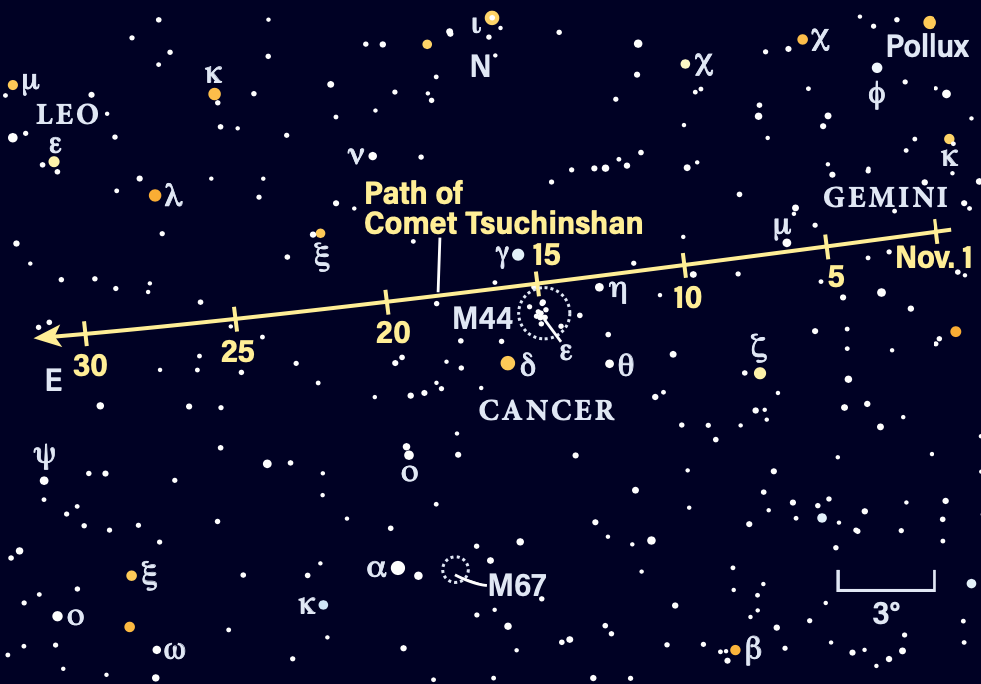

Comet Tsuchinshan slides past the Beehive Cluster (M44) midmonth, offering an excellent scene for astrophotographers to capture. Credit: Astronomy: Roen Kelly

Wednesday, November 15Comet Lemmon may be stealing headlines, but it’s not the only comet worth your attention. Comet 62P/Tsuchinshan 1 is offering up a beautiful scene as it pairs with the glittering Beehive Cluster (M44) in Cancer today. You can either catch it high in the south in the early-morning hours before dawn, or late tonight in the east as it rises in the hour or two before midnight.

Let’s focus on the early-morning appearance first. Cancer lies nearly due south around 5:30 A.M. local time and is some 70° high. In the center of the constellation is the Beehive, a young open cluster of stars visible to the naked eye as a fuzzy patch of light with a few resolved pinpoints.

This morning Tsuchinshan — last spotted around magnitude 11 — lies less than a degree north of the center of the cluster, flying through its outskirts. It’s a beautiful view through a telescope and a great opportunity for astrophotography, which will pick up the fainter comet even better. In photographs, the comet should glow green — it’s close enough to the Sun for diatomic carbon to form a coma around the nucleus as organic material breaks apart under the onslaught of solar photons. Consider using a 135mm telephoto lens to capture a memorable photo of the scene.

By this evening, the comet will have moved east, sitting slightly northeast of the center of the cluster but still within 2° and ready for even more photo ops. Cancer rises around 10 P.M. local time and you should be able to catch sight of the pairing low in the sky about half an hour later — but waiting even longer for the constellation to climb higher will offer even better views, as long as you’re willing to stay up late.

Sunrise: 6:45 A.M.Sunset: 4:44 P.M.Moonrise: 9:25 A.M.Moonset: 6:15 P.M.Moon Phase: Waxing crescent (6%)

Thursday, November 16Now it’s Mercury’s turn to pass Antares, moving 3° north of the star at 1 P.M. EST. Again, however, the pair is not readily visible, as Scorpius is still setting too soon after the Sun to give Antares time to shine. Mercury, however, may be a bit easier to see than it was on the 14th, now 3° high 20 minutes after sunset as it moves quickly through the sky. You’ll still need a clear southwestern horizon to see the planet, still magnitude –0.5 and likely to stand out in the falling twilight to a sharp eye, and appear readily in binoculars or telescopes.

Mercury currently lies 1.3 AU from Earth and appears 5″ wide in a telescope — note that this is slightly larger than the apparent width of Uranus, which in reality is much, much larger but also lies much, much farther away. Because it circles the Sun inside Earth’s orbit, Mercury appears to go through phases. It is currently 90 percent lit, nearly full. Over the next several weeks, it will wane, with less and less of its face lit by the Sun. Watching this occur can be a fascinating experience, so be sure to check out Mercury in the evening sky every few days throughout the month as it travels from Scorpius to the east up through Sagittarius, the next constellation along the ecliptic.

Sunrise: 6:46 A.M.Sunset: 4:43 P.M.Moonrise: 10:29 A.M.Moonset: 7:15 P.M.Moon Phase: Waxing crescent (13%)

A Leonid streaks across the sky near Orion during the 2020 shower. Credit: David Wipf (Flickr)

Friday, November 17The annual Leonid meteor shower peaks overnight tonight; the best time to view it is early tomorrow morning when Leo is high in the sky, but if you’re an evening observer, there will still likely be some meteors to catch as the shower ramps up to its maximum.

The radiant, where shower meteors appear to originate, is near Leo’s head, which is first to rise in the hour before local midnight. Plus, the crescent Moon sets around 10 P.M. local time, leaving the late-night sky dark and ideal for spotting shooting stars. Because shower meteors look best — i.e., typically have the longest bright trains through the sky — a little ways away from the radiant, you’ll be best served by looking near Gemini and up into Orion and Taurus, all of which rise earlier and lie well above the eastern horizon before midnight.

The Leonids’ maximum rate isn’t particularly high — just 10 meteors per hour at best — so this won’t be a stunning meteor storm. Still, these are particularly fast-moving meteors that often leave long, glowing trails of ionized gas in the atmosphere. So, if you spend a while outside late tonight or early tomorrow morning, you’re likely to see at least a few memorable meteors streak across the sky!

Sunrise: 6:47 A.M.Sunset: 4:42 P.M.Moonrise: 11:25 A.M.Moonset: 8:24 P.M.Moon Phase: Waxing crescent (21%)